4.4.2024

INNER WARRIORS

Like visual maps of our psychologies, Inner Warriors explore the defence mechanisms we deploy in order to survive, the contradictions, the little rituals, the bouts of self-destruction that make us human.

For this series I have gone back to what excites me the most in image making which is story telling. Using a range of favourite imagery from popular culture, folklore and fairy tales, the artworks are packed with playful little narratives.

From the Yogi-Barbapapa sitting on cacti, to the kiss-traps ready to ensnare those who come too close, each accessory or tattoo adorning the warriors acts as a protective talisman.

These women are guardians and stand strong. They protect the “inner child”, the vulnerability, the freedom, the play, and the irreverence, all notions crucial to creativity and that I deeply care about.

The Inner Warriors collection was launched at The Other Art Fair Los Angeles in April 2024

TLC | 23.2.2023.

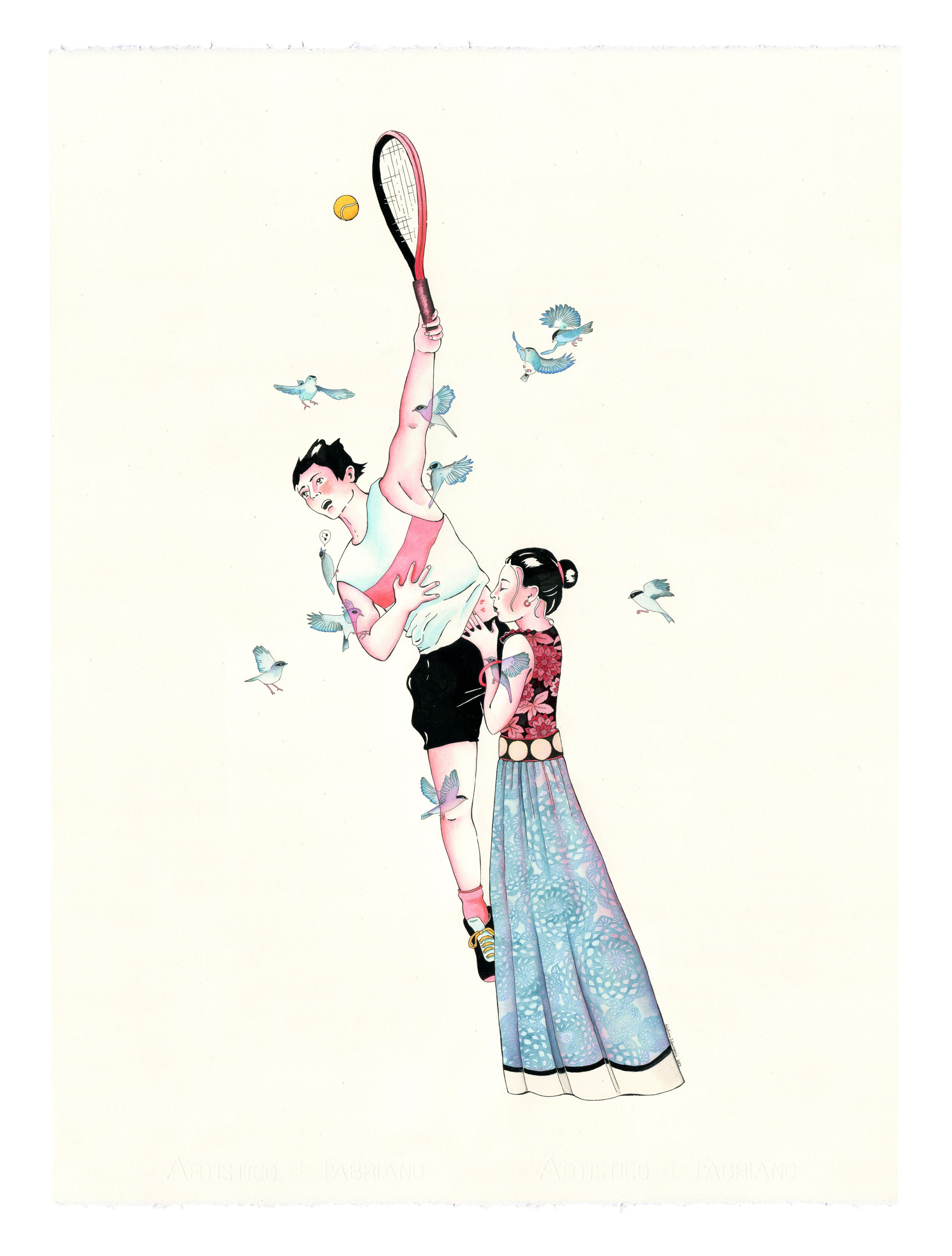

TLC is a new collection of 20 original drawings about our relationships, the anatomy of our longing for one another, and the fragility of connection.

Each drawing involves characters taking a shot at love, and yet remaining in parallel universes.

The series explores the unrequited nature and the impossibility of sharing, with tenderness as a silver lining.

The result remains charming and humorous, a patchwork of visual references spanning from classical painting to comic books and manga.

20th April 2022

BEAST

New Collection

In 100 years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, one of the characters, Rebeca, eats dirt whenever she is feeling distressed, a concept I find fascinating. Like any food or drink craving, her taste for soil is a surrogate for emotional contentment. Yet in my eyes, this behaviour also unites her with the earth and the animalistic traits that are common to us all.

From vampire stories to popular folklore, mythology to Marvel comics, the list of characters half-man, half-animal is endless and serves as a reminder of our most primal instincts. The animal gives its strength, turning the man into a super being, while simultaneously casting him out of society.

Looking at primal behaviour and compulsions, cinema is, of course, the obvious artistic form to look at. Films like Swallow (Carlo Mirabella-Davis), Beast (Michael Pierce), As Boas Maneras (Juliana Rojas and Marco Dutra), Furie (Olivier Abbou) and even Twilight (Catherine Hardwick) all explore hidden and intimate urges that threaten social norms with their violence and inadequacy.

When Julia Ducournau received her Palme d’or for “Titane” last year, her speech resonated with me, especially when she spoke about recognising the monster in us. Before Titane, Ducournau directed the brilliant “Raw”, a coming of age horror film about a girl who develops a taste for human flesh.

From a psychological point of view, what we eat and what we drink reflects our mental state, and creatively it also acts as strong metaphorical tool for unexpressed emotions. This is a theme that I have explored in the past with pieces like “Ogresse” or “Dog Woman” (after Paula Rego).

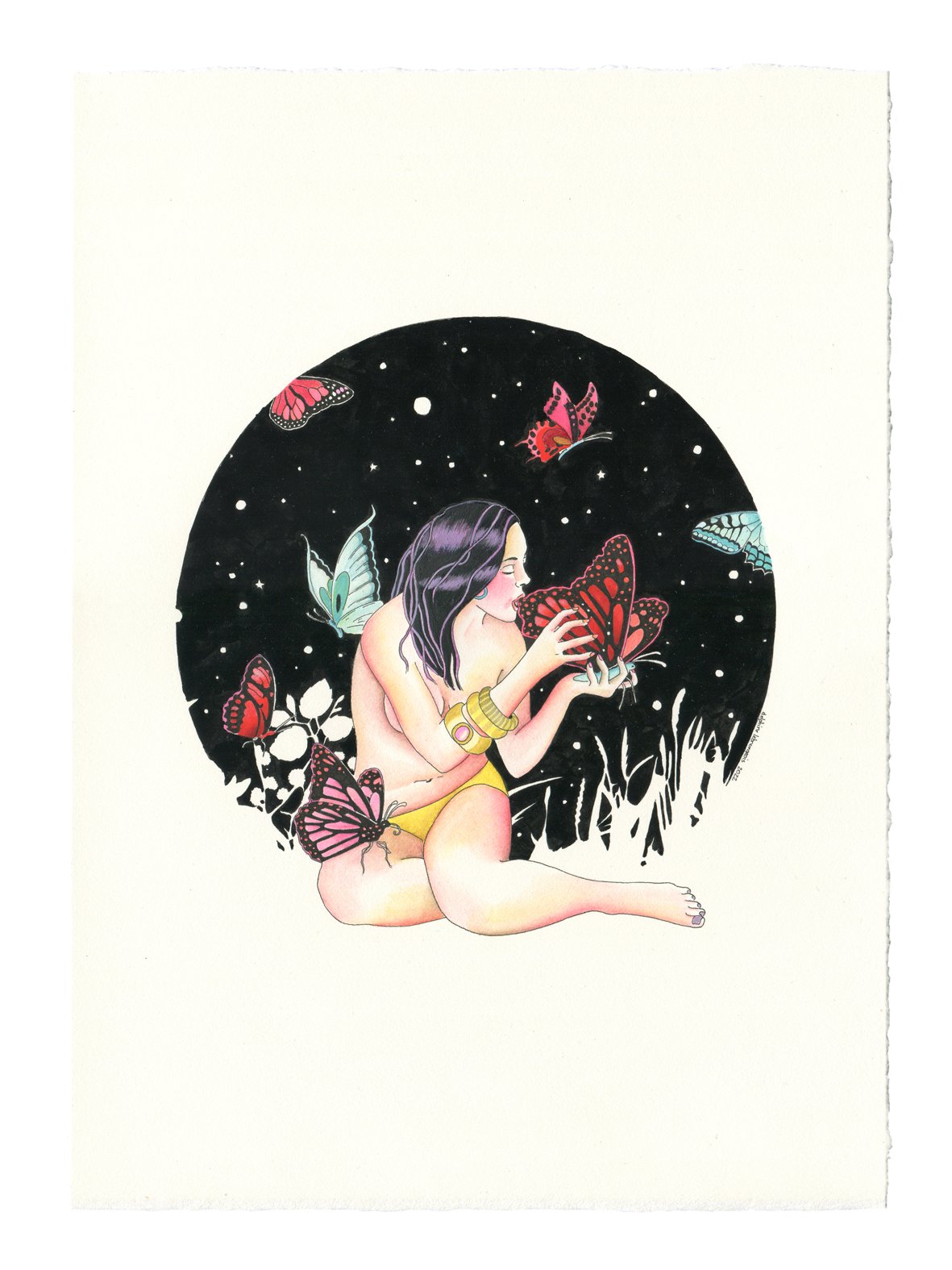

In “Papillon Mon Amour” and “Solo Eater”, the woman bites into a large butterfly. Beyond the desire to symbolically destroy the ‘cute’ and the pretty, generally associated with butterflies (and with women), I also wanted to question the viewer: who is the Beast - the monster? The abnormally sized butterfly? The woman behaving “inappropriately”? Or neither?

Beast is an exploration of the darker emotions present in all of us, with a particular focus on women. The fictional characters I choose to portray own their freakiness and their difference with no shame. They are calm, unapologetic and in control, reminding us that it’s all right sometimes, to not abide to social norms.

VIEW WORKS

26th August 2021

THE GUARDIANS

Outdoor project / Ambert / France / August 2021

I'm very pleased to introduce “The Guardians”, my first outdoor project and installation. Pre-pandemic, I lived between London and my partner’s home in a hamlet near Ambert, where the piece is available to view for all passers-by.

Though this nomadic lifestyle was a challenge when trying to find a sense of belonging, it nonetheless offered a certain balance and the best of both worlds. The pandemic however, altered this rhythm drastically, and following a year of lockdowns and quarantines in a small London flat, I needed to reconnect with nature and simply get a sense of breathing again.

Exhibiting in the wild had been on my mind for some time. “The Guardians” is my first attempt. I chose the Amazonian figures for their obvious symbol of femininity and protection. Printed on paper and pasted on recycled cardboard, the figures are extremely fragile and prone to weather degradation. The project had to be ecological and ephemeral.

Like street art in cities, when it comes to art in nature, you can either search for it (if you know it exists), or discover it by chance, which is the aspect that interests me the most. For this specific project, I chose a remote part of nature. The location of the exhibit is hidden in the woods, away from touristic trails, and with very few people usually passing by.

Hopefully, the fleeting apparitions will create a certain surprise in the viewers, reminiscent of childhood discoveries: a colourful Easter egg under a leaf, an edible mushroom hidden in a heap of moss, a shiny beetle to capture and keep. Something to do with the magical...

12th April 2021

ALL HYSTERICAL

Press Release

Edited by Juliette Howard

Dating back centuries, hysteria has always been perceived as a predominantly female issue. Ancient Egypt attributed it to a wandering uterus (from which its name derives) and in the Middles Ages right through the Renaissance, Christian beliefs often associated hysteria with satanic possession or witchcraft, leading to thousands of executions.

In the late nineteenth century, French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot studied hys- teria at the Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris, where he “treated” over one hundred and twenty women. Through dramatic public demonstrations involving hypnosis, Charcot displayed “hysterics” as fabricated performances, surrounding himself with writers, artists and filmmakers to document his research. The spectacular nature of female spasmodic bodies fascinated, and inevitably inspired numerous artists such as Auguste Rodin, Edgar Degas and Toulouse Lautrec. The influence of the “hysterical trend” also appeared in theatres with Jane Avril (who was one of Charcot’s patients) and Sarah Bernhardt.

Even if Charcot (closely followed by Sigmund Freud) acknowledged the existence of male hysteria, his patients were almost all women, subjects more easily exploitable and more aesthetically pleasing for the Salpêtrière’s all male audience.

Today in Western culture, hysteria is disregarded as a medical diagnosis. The term ‘hysterical’ is still tinted with negativity, often referring to a person who is un- controllably emotional or irrationally upset. Since the 1960s however, many feminists have been looking at hysteria as the first, unconscious attempt to confront patriarchal values, a language women used in an attempt to be heard and noticed.

Delphine Lebourgeois’ new series of works “All Hysterical” is an exploration of phe- nomena often associated with teenage girls – such as fandoms and conversion dis- orders – as well as a broader rendition of teenage years in general. Inspired by literature, Beatlemania, K-Pop fans and various accounts of conversion disorders (including multiple cases of Tourette’s syndrome amongst a group of cheerleaders), she depicts adolescence as an age of intensity, mystery and transition, turning “hysteria” into a strength and a super-visionary state. The adolescents are portrayed as forces of nature with a clear sexual undertone, slurping at a tornado as though it were an ice-cream, brooding in the crater of an erupting volcano or biting ravenously into a K- pop boy band.

Despite the ‘out of control’ nature one would expect from hysterical behaviour, most of Lebourgeois’ images are particularly serene - a paradox considering its subject. Her carefully crafted compositions rather seek to impose a sense of control and calm, so that the so called hysterics instead appear to master their bodies and minds.

In the “All Hysterical” drawings and Cheerleaders series, Lebourgeois borrows a Paul Richer drawing - “Arc de Cercle” - dating back to 1887 and originally published in a book the artist-neurologist co-wrote with Charcot, “Les Démoniaques dans l’Art”. The black and white medical drawing portrays the body of a helpless and distressed woman, arched backwards as though in agony. Lebourgeois turns this notion of vulnerability on its head, subverting its original meaning and purpose in order to transform the otherwise passive body into an active one. Illness turns into a force.

Much like her 2020 series Witches, “All Hysterical” is another account of female re- pression that Lebourgeois explores, plays with, and ultimately dismantles, always with a degree of humour but never downplaying the importance of positioning her female subjects as the true bearers of power.

18th January 2021

Fits

When I was seventeen, it was a recurring phenomenon for girls in my class to have fits in the middle of lessons. This started with one of the popular girls, Cécile, and soon spread across to other female pupils, reaching out to the more discreet ones. The fits were particularly violent and necessitated for the girls to be carried out of the classroom, often by two of the strongest boys and down the three flights of stairs to the infirmary. Cécile had the most dramatic episodes and they usually sparked some kind of contagion. The other girls’ symptoms however were not as spectacular, and seemed to decrease as the contamination evolved from one girl to the next.

One day, seven girls started fitting nearly simultaneously, disrupting the lesson beyond repair under the eyes of a weary and bemused English teacher.

The boys rushed up and down the stairs taking one girl at a time, getting kicked along the way by the spasmodic bodies of their female counterparts. It was wild and strangely comical.

This took place in a Catholic school, during the year of the Baccalaureate, a time filled with pressure, never-ending lessons, and a vivid eagerness to escape the classroom and school life all together.

As one of the few “non-contaminated girls”, I felt together amiss, jealous and entertained. I could sense the release expressed by their bodies. Release of frustration, of sexual tension, of boredom, and I shared all of those, despite being unable to express them in a physical way. The fits, in all their theatrical glory, also attracted the attention teenagers have always craved. Being lifted out of the classroom, rescued by two handsome young men under the eyes of a small crowd, filled me with envy back then.

We were not aware of “conversion disorders” and didn’t reflect on it. It was just an unexplained thing that happened to them, but somehow, there was a link between the girls affected, a common understanding which pushed the others away from a sense of belonging.

At the time, I wished I had been one of them.

Mania / 2019 / Ink, watercolour, acrylic and collage on paper / 70x70cm

October 2020

Bright New World

New Collection

I’m really pleased to introduce this new series of original drawings created over the last few months

Unlike other projects, this one has grown really intuitively starting with Spring Quarantine back in April and evolving along the way

There were many things I wanted to talk about: The hope and the opportunity for change that every crisis brings, the idea of a sanctuary, the gentle trauma of the confinement and the way we sometimes go back to our childhood in the face of adversity, as well as of course, our relationship with nature…

It’s probably my most intimate series so far, and yet it’s also very much looking out to the future.

April 2020

Witches

New collection

PRESS RELEASE by Juliette Howard

The figure of the witch has been present for hundreds of years, and behind the folklore and popular culture, there are centuries of terror for women. Being accused of witchcraft in the sixteenth or seventeenth centuries for instance was as good as a death condemnation. In times of crisis, witchcraft was too serious to take any risks: if a significant amount of people asserted a woman was a witch, then that was enough evidence. Deaths multiplied, women lived in fear of being denounced for something they were not. What remains striking is that none of them were able to defend themselves once the decision was made. Voiceless, they were burnt at the stake as demons.

Lebourgeois’ new body of work – “Witches” – is an echo to the current liberation of women’s speech and a reminder that far from being acquired, women’s rights and parity between men and women still have a long way to go. In this respect, Lebourgeois is particularly interested in the political implications of the contemporary witch. Today, this figure represents the ultimate rebel. She is the woman who isn’t afraid to speak out, the woman who is herself no matter what, the woman liberated from patriarchal archetypes. Modern witches defiantly stand up to injustice and demand a fairer balance within society – but this does not come without a cost. In her book “Witches: the unbeaten power of women”, Mona Chollet explains that women who do not fit the mould are still as oppressed as they were in the past. Women who refuse to have children, single women and old women especially fall victims to a judgemental society.

Reading around this subject, Lebourgeois realised that the figure of the witch, burnt in the past, oppressed in the present, who now chooses to shout back, perfectly embodied the notion of female empowerment that is so crucial to all of her work. Indeed, Chollet is part of a movement of women – French women in particular – who have, to put it simply, had enough. Alongside the #metoo movement, feminists like Virginie Despentes and Adele Haenel – who walked out of the Cesar ceremony after Roman Polanski won Best Director – have greatly influenced her art and inspired a new facet to her armies of women.

Lebourgeois often uses humour in her work and this series is no exception: a wicked weapon for a cause important to her, the light-hearted fun reminiscent of childhood and games that gives the images a carefree feel is not an obstacle for the armies of women, but what they ultimately need to protect. Their inner child is not just a child, but their vulnerability, their freedom, their creativity and ultimately their power. Thus, a witch lighting a cigarette from the flame that is to burn her alive is comically giving the finger to the society who tied her to the stake in the first place.

However what remains most crucial is that this witch is not alone. The idea of a group often repeated in Lebourgeois’ work has a political dimension that is both important to her and to the female cause: these women are strong-willed, but the little child always protected by their wall of fists and swords does not exclude their vulnerability or maternal instincts. Her images are a celebration of diversity and difference, of being whoever we wish to be without judgement. It is not a question of conforming: it is always a question of choice. The powerful image of women marching in the same direction, shouting for one, united wish testifies to the energy and strength of communal force: it is a way of being heard together, no matter who we are.